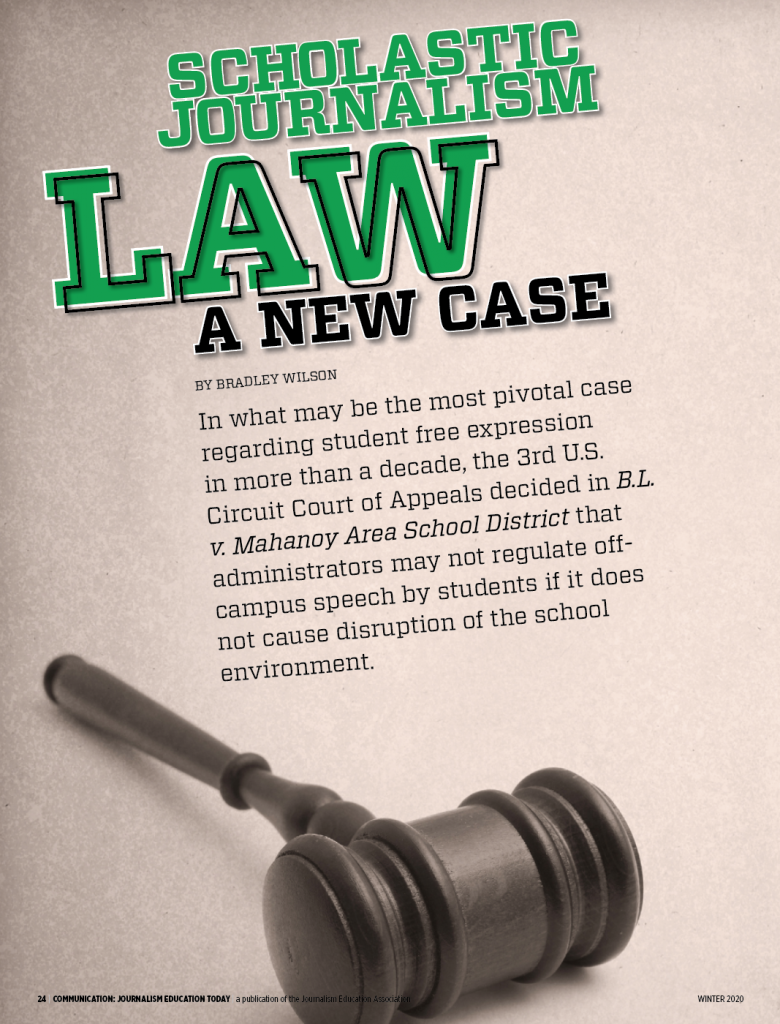

B.L. v. Mahanoy: A New Case in Scholastic Journalism Law

WATCH ORAL ARGUMENTS OF THIS CASE ON C-SPAN APRIL 28, 2021.

In what may be the most pivotal case regarding student free expression in more than a decade, the 3rd U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals decided in B.L. v. Mahanoy Area School District that administrators may not regulate off-campus speech by students if it does not cause disruption of the school environment. The Supreme Court will hear the case on April 28, 2021.

Summary

As indicated in the initial letter to the school district from the American Civil Liberties Union on Sept. 1, 2017, by attorney Molly Tack-Hooper to school Superintendent Joie Green with the original text uncensored:

B.L. was punished for a social media post she created in Snapchat with the text “f— school f— softball f— cheer f— everything.” She created the snap on the weekend, off campus, at a time when she was not participating in cheerleading or any school activity. The snap did not mention the school district, any particular sports team or any person. She shared the snap only with her friends, about 250 people. It was not accessible to the general public.

To be sure, B.L.’s snap was crude, rude, and juvenile, just as we might expect of an adolescent. But the primary responsibility for teaching civility rests with parents and other members of the community. Cheryl Ann Krause,judge, 3rd Circuit Court of Appeals

Opinion

Written by 3rd Circuit Judge Cheryl Ann Krause:

Public school students’ free speech rights have long depended on a vital distinction: We “defer to the school” when its “arm of authority does not reach beyond the schoolhouse gate,” but when it reaches beyond that gate, it “must answer to the same constitutional commands that bind all other institutions of government.” Thomas v. Bd. of Educ., 607 F.2d 1043, 1044–45 (2d Cir. 1979). The digital revolution, however, has complicated that distinction. With new forms of communication have come new frontiers of regulation, where educators assert the power to regulate online student speech made off school grounds, after school hours, and without school resources.

This appeal takes us to one such frontier.

Appellee B.L. — a minor and then a freshman at Mahanoy Area High School (Mahanoy City, Pennsylvania) — failed to make her high school’s varsity cheerleading team and, over a weekend and away from school, posted a picture of herself with the caption “f— cheer” to Snapchat. She was suspended from the junior varsity team for a year and sued her school in federal court.

The District Court granted summary judgment in B.L.’s favor, ruling that the school had violated her First Amendment rights. We agree.

Commentary

When the decision from the 3rd Circuit (District of Delaware; District of New Jersey; Eastern District of Pennsylvania; Middle District of Pennsylvania; Western District of Pennsylvania; District of the Virgin Islands) came down over the summer, it was hailed as a victory for students, a historic decision.

Adam Goldstein, senior research counsel for Foundation for Individual Rights in Education, said, “I’d argue that not only is the decision historic, but it’s historic for at least two reasons. The first is the willingness to actually say that, no, schools don’t control off-campus speech — that ‘student’ status is not an impairment on their rights as citizens out in the world. The second, equally important part of the decision is finding that extracurricular activities, including athletics, are integral parts of the educational process.”

More on Goldstein’s second point later.

The National School Boards Association, through Chief Legal Officer Francisco Negrón Jr., had a different view.

“This case is about a school’s ability to fulfill its educational mission, including the teaching of social norms like leadership, teamwork and good conduct through extracurricular activities,” he said.

Sara Rose, senior staff attorney with the ACLU of Pennsylvania, continued on that idea.

“Public schools need to recognize that there are limits to their authority to control students’ speech when they are outside of school. Schools not only have an obligation to teach students about ‘good sportsmanship,’ as the District has asserted in this case; they also have an obligation to teach students about their constitutional rights. That includes teaching them that they have the right to say things that the government may not like – even when it may harm ‘morale.’ Students should take away from this case that their speech is entitled to full First Amendment protection when they are outside of school.

“But the case also serves as a warning about the perils of speech on social media: Even if you write something that is shared with a small number of your friends and will disappear after a certain amount of time, it can still be shared by people whom you did not intend to share it with,” Rose said.

With that foundation, let’s get back to Goldstein’s first point.

Frank LoMonte, professor and director of the Brechner Center for Freedom of Information at the University of Florida, said, “It’s incredibly important for student journalists, activists and whistleblowers that a court has finally recognized that a school does not have the same level of control over off-campus speech on personal time that applies to on-campus speech during instructional time. If students were limited to the level of First Amendment protection recognized in the Tinker case during every hour of the day, year-round, then there would literally be no time or place that a student could confidently criticize the school without fear of retaliation.”

It was a case fought by a then 13-year-old Mary Beth Tinker (among others) who, in 1969, fought all the way to the Supreme Court to show that Warren Harding Junior High School could not punish her for wearing a black armband in school to support a truce in the Vietnam War. The Tinker case had been a standard for half a century, despite the changes in the media.

LoMonte said, “The most dangerous aspect of the Tinker standard is that a school can legitimately punish a student under Tinker even without proving any wrongful intent to disrupt the school. So if a student gives a political speech during a school assembly that provokes the audience into a fistfight, the student loses First Amendment protection even if the listeners are overreacting and even if the student had no intention of causing the fight. Imagine extending that level of control to every waking hour of a young person’s life. A principal could order a student gay-rights activist to pull down a video from a personal YouTube channel if the principal anticipates that homophobes will attack the student activist at school. A principal could punish a student for picketing outside the school board offices for the removal of a pedophile coach if the principal anticipates that the protest will provoke a flood of phone calls from outraged parents. That can’t possibly be how the First Amendment works, and thankfully the 3rd Circuit has said so.”

The second part of the ruling is also pivotal to the case.

Goldstein said, “[F]or too long, schools have tried to leverage access to extracurricular activities (including, in some cases, journalism activities) to coerce students into surrendering rights they would otherwise have, such as the right to post negatively about their school experience on social media. They got away with it by arguing that there was no obligation to permit access to extracurricular activities that were not, in short, part of the educational experience the school was obliged to provide. By recognizing that extracurricular activities are part of a school’s educational offerings, the court recognizes that they cannot be arbitrarily withdrawn, or have access to them limited by unconstitutional restrictions, even if they have the veneer of a contract.”

LoMonte agreed.

“It’s important that the judges were not swayed by the existence of a so-called First Amendment waiver that purports to entitle the school to discipline any speech they find inappropriate or critical. You can’t condition participation in a school activity on a blanket waiver of constitutional rights. You couldn’t make a cheerleader sign a waiver allowing the coach to come to her house at any hour of the day or night and conduct a strip-search. You couldn’t make a cheerleader sign an agreement compelling her to attend church every Sunday as a condition for taking part in extracurriculars. This is just common sense, but too many schools have asserted themselves into the off-campus lives of their students by demanding that they adhere to “niceness contracts” that are aimed at suppressing criticism of the school. Public schools are government agencies, and people get to criticize the government — even if they use ‘inappropriate’ language — and the government can’t punish that criticism by withholding a benefit.”

Negrón said both sides are important.

“The court should acknowledge the importance of the nexus between out-of-school conduct and the school setting, whether that setting is the classroom or in the many other school-related activities that are part of the educational mission,” he said.

He continued.

“When it comes to student activities that are a privilege and not a right, as with academics, schools have greater deference in requiring specific conduct from students. In part, this requirement is an essential part of teaching young people how to develop leadership skills, nurture teamwork, and build social skills that prepare students for their future as productive members of -society.”

Seth Kreimer, an expert on constitutional law and professor at the University of Pennsylvania Carey Law School, summarized the general feelings on the case. “The opinion strikes me as a well-thought-out opinion that gives important and sensible guidance to both students and school administrators,” he said.

Mahanoy Superintendent Joie Green said simply, “I have no comment at this time.”

After the case was appealed to the Supreme Court, the attorney representing the school district, Lisa Blatt, said, “I am sorry. I cannot comment.”

However, Negrón elaborated on why he thought it was important for the top court to hear the case.

“In addition to academics, schools also inculcate social values and norms. These include skills that can prepare students for college and career readiness, including leadership, teamwork, collegiality, appropriate conduct, to name a few,” he said.

In one sentence

Coaches cannot punish students for what they say off the field if that speech fails to satisfy the Tinker or Hazelwood standards.

What’s Next

On Aug. 28, 2020, the school district petitioned to have the case heard by the Supreme Court, challenging the court to answer “whether Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District, 393 U.S. 503 (1969), which holds that public school officials may regulate speech that would materially and substantially disrupt the work and discipline of the school, applies to student speech that occurs off campus.”

Rose said, “If the Court agrees to take the case, then it will be the first decision issued by the Supreme Court regarding schools’ authority over off-campus student speech.”

In January of 2021, the Supreme Court agreed to hear the case on April 28, 2021.

REUTERS: “U.S. Supreme Court ponders cheerleader’s profanity in free speech flap“

EDUCATION WEEK: “7 Things to Know About the Cheerleader Speech Case Coming Up in the U.S. Supreme Court“