Leading with life: Tips from “Since Parkland”

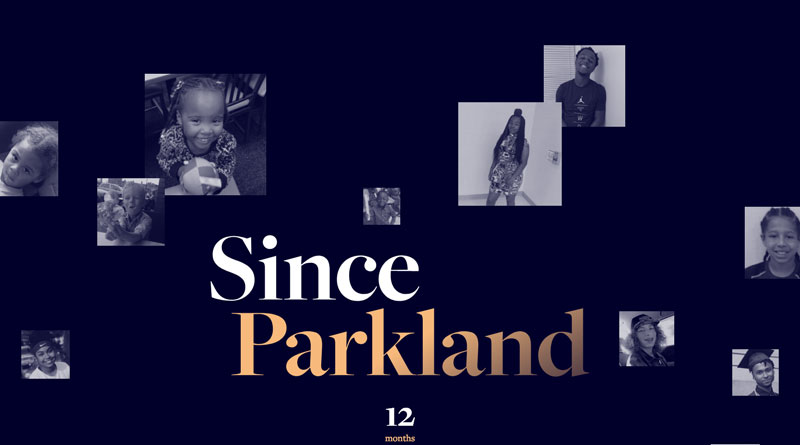

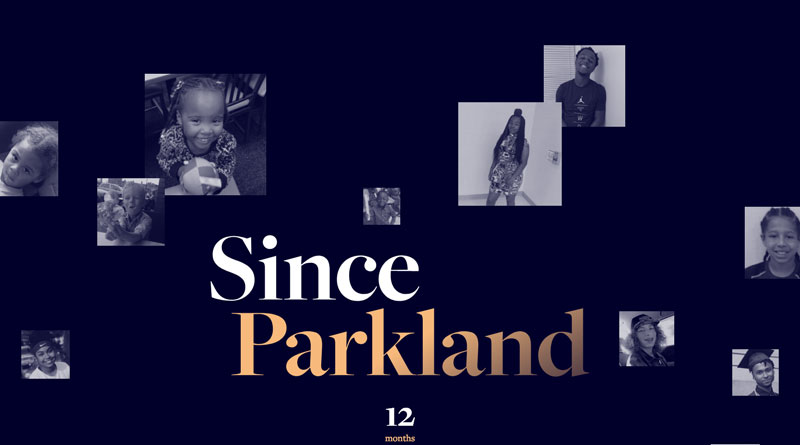

The landmark Since Parkland project — in which student journalists produced 1,200 portraits of children and teens killed in gun violence in the year after the shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School — was a crash course in reporting, researching and writing a story that even veteran journalists find difficult to tell: the obituary.

Published by The Trace and the Miami Herald on Feb. 12, the project involved the work of more than 200 student journalists around the country, many of them working in a virtual newsroom supported by regular video conferences and an online curriculum with resources and readings.

The scope and urgency of this project, which began in earnest in September 2018 with a backlog of 800 data links — each of them representing a young life lost since Feb. 14 — and a deadline in early February 2019, created a push for tips and tools that students could use quickly, especially when trying to go beyond the who-what-when-where of a death.

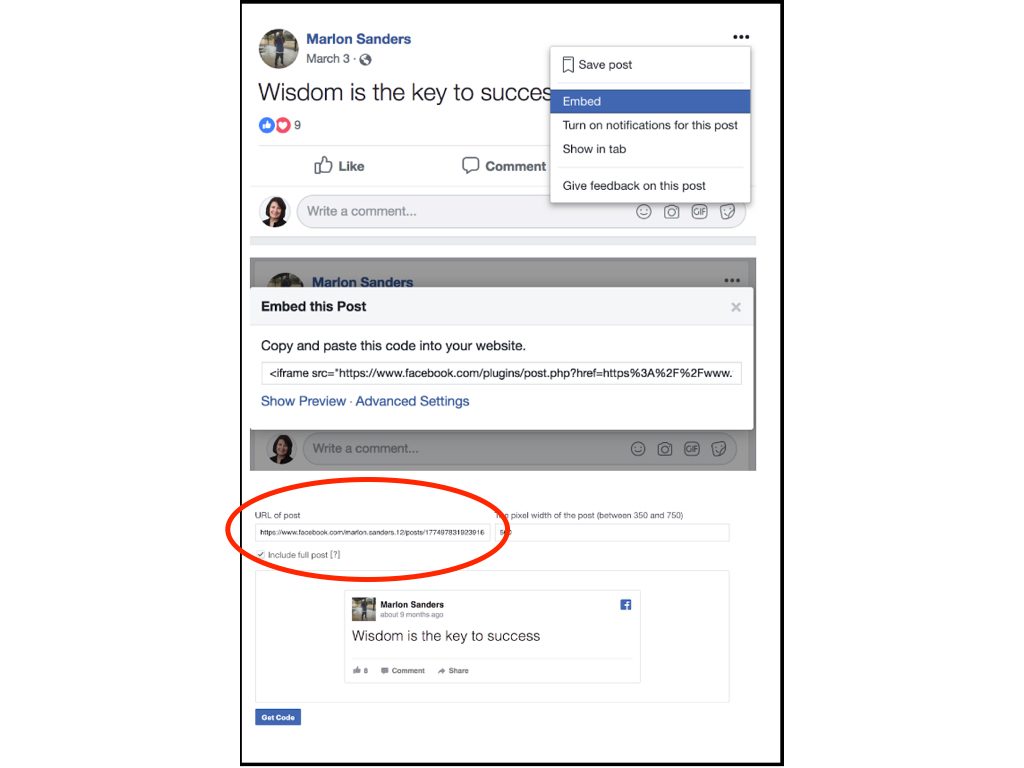

For example, Facebook became a go-to resource for personal details, including names of family and friends, and hundreds of posts, images and comments. But how to hyperlink to a particular post that could be fact checked by editors, and not the entire feed?

Searching through the advanced settings one weekend, I found that grabbing the URL offered at the embed page would hyperlink back to the desired post:

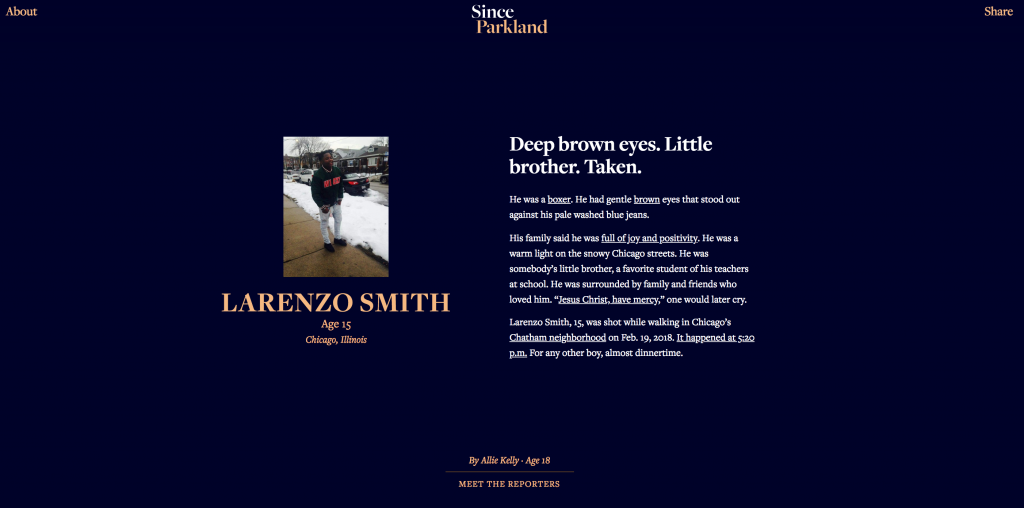

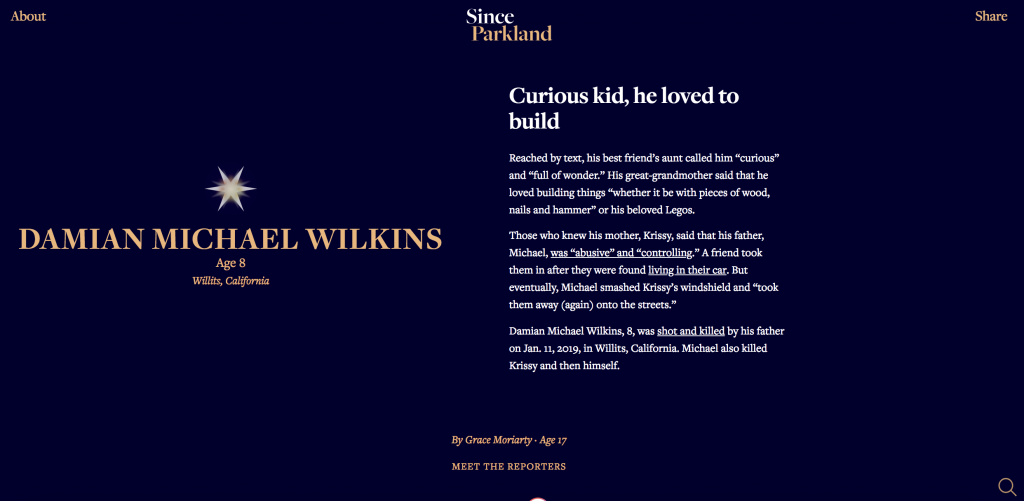

There were other finds. Lives (and deaths) that were scant on facts — think a young black man killed on a Saturday night in Chicago — prompted some students to develop ways to create a sense of place. Weather data, Google Street View and real-time images became one way to develop details such as “snowy Chicago streets,” as in this story by student Allie Kelly, which was written months before Larenzo Smith’s family shared his photo:

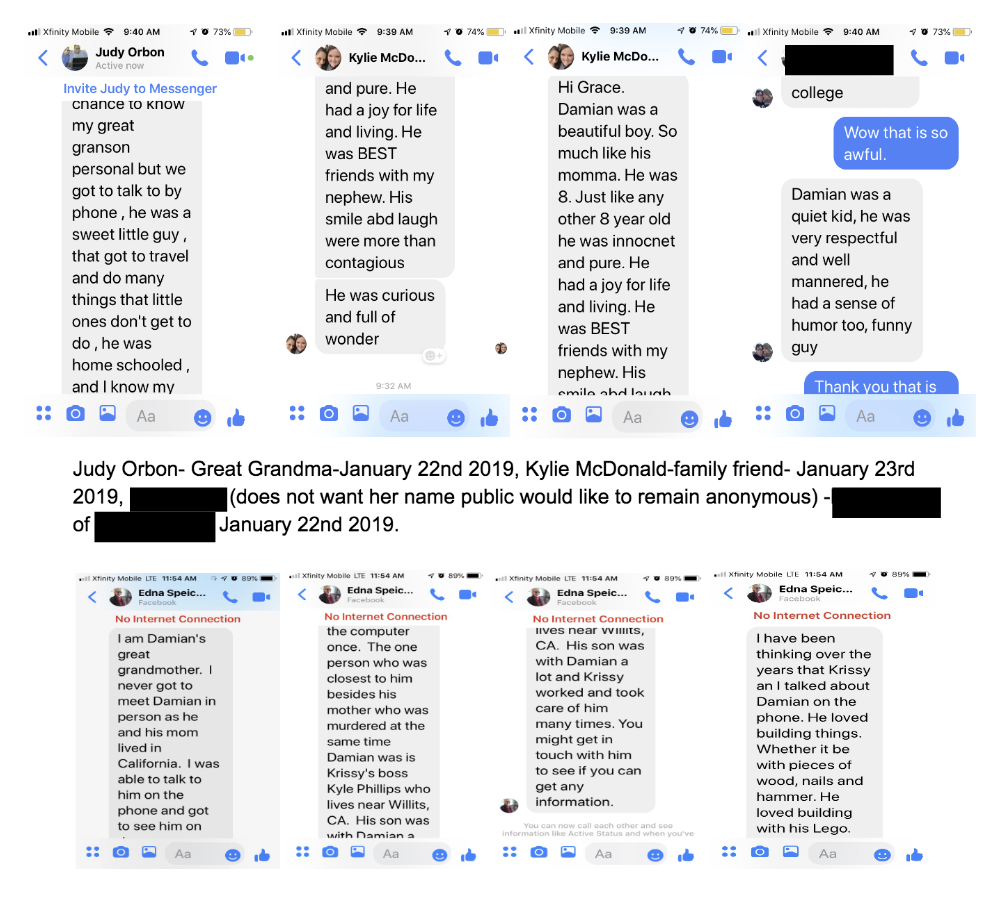

Perhaps most extraordinary, students used social media to reach out to families and friends of gun victims, sometimes getting access to private Instagram accounts, and conducting interviews by text and direct messaging via Facebook, Messenger, Twitter, WhatsApp and other texts.

But verifying such conversations was necessary. Independently, students began placing screenshots of the accounts and/or conversations into their story drafts so that editors could check quotes and paraphrases:

Over time, our understandings became part of a crowdsourced Reporting and Fact Checking Resources Guide, including help from Trace and Herald investigative reporters, student editors and senior project editor Katina Paron and myself. Below is the entry on hyperlinking to Facebook.

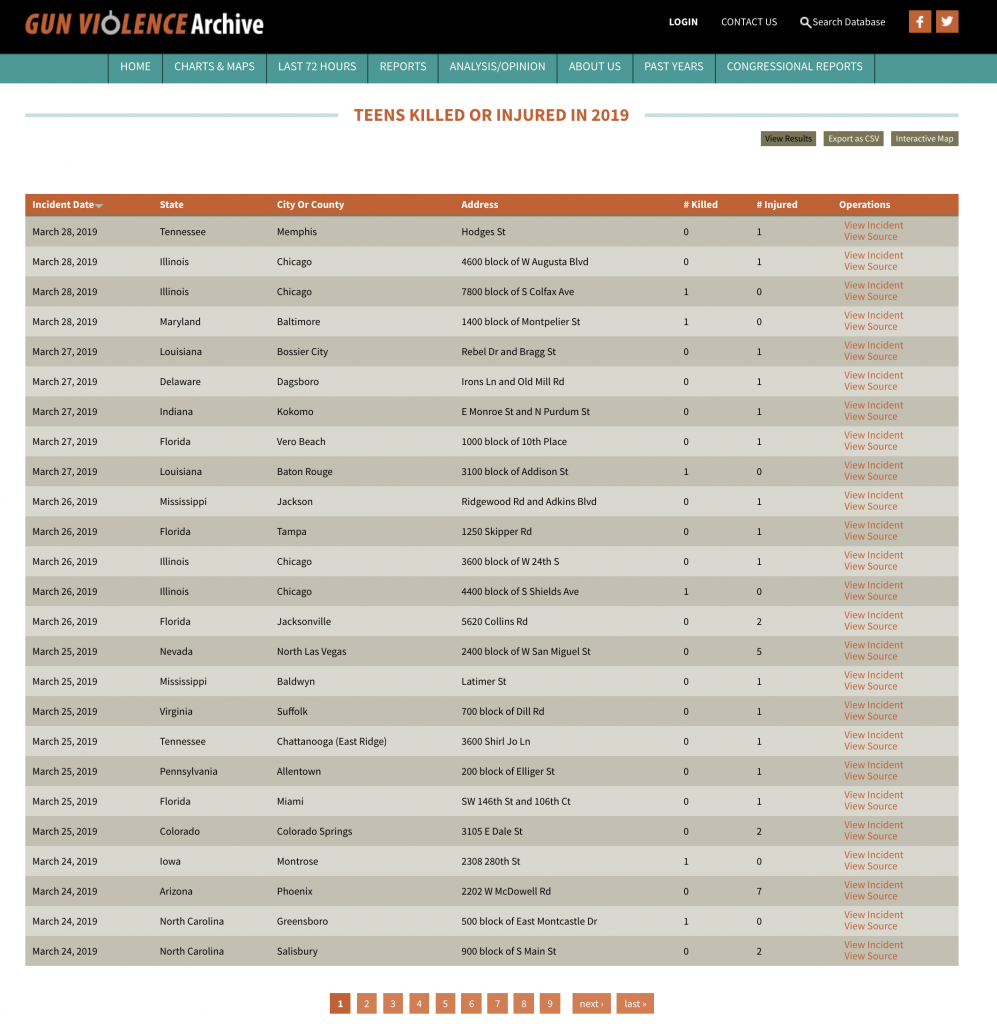

A special note: If you would like to replicate the process behind Since Parkland in your own classroom, you can. The nonprofit Gun Violence Archive tracks gun injuries and deaths on a daily basis, organizing them by age and geographical location, including URLs to print, television and online news reports about the death and geotags to the place where it happened:

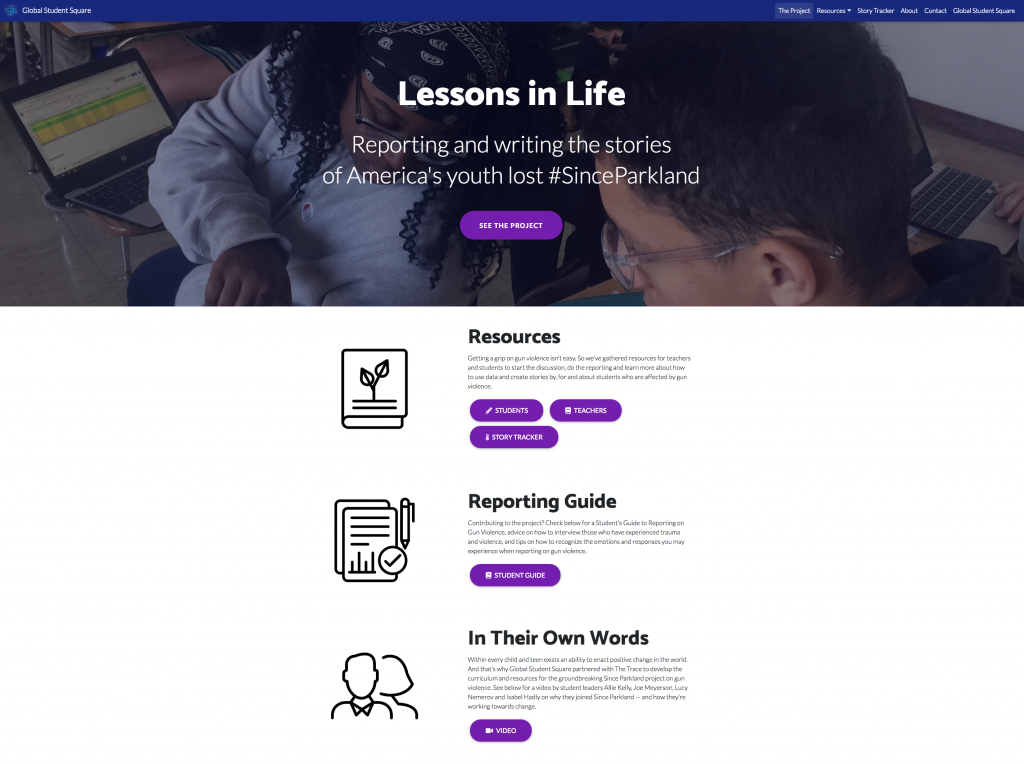

The Trace’s Story Template for the project guides students step-by-step through the flipped obituary format. A “Lessons in Life” toolkit includes lesson plans, handouts, checklists and other resources for teachers and students:

Though these are sensitive stories and must be sensitively told, reporting and researching how young people die from gun violence puts a human face on the statistics behind a social issue. And stress builds when bad things happen but others feel they can do nothing. Among the student journalists we worked with, Katina and I saw agency and purpose as they learned, wrote and remembered young lives lost.

Your suggestions and comments are welcome — please send them to beatrice@globalstudentsquare.org and they’ll be added to the guide for future reporters.

—Beatrice Motamedi, senior project editor and curriculum developer for Since Parkland and director, Global Student Square

How to embed a Facebook post

To hyperlink directly to a Facebook post and not the whole page, do this:

1. Click the three dots in the upper right-hand corner of the post

2. Select “embed”

3. Do NOT “copy and paste” the code. Instead, click on “Advanced Settings”

4. A screen will come up with the URL of the embed. That is a hyperlink. Grab it.

5. Test your hyperlink by opening a new tab and going to the link (the post you want should pop up).

Extra credit: Note that you can include the date of the post in your story.

“If you truly love someone, (then) the only thing you want for them is to be happy even if it’s not with you,” she wrote on her Facebook page on Aug. 28, 2017. “If someone truly loves you they will never let you go no matter how hard the situation is. (J)ust have hope, faith and joy.”